Student-Athletes: I, For One, Support You

Why athletes, in the midst of college admissions chaos, deserve to go where they go.

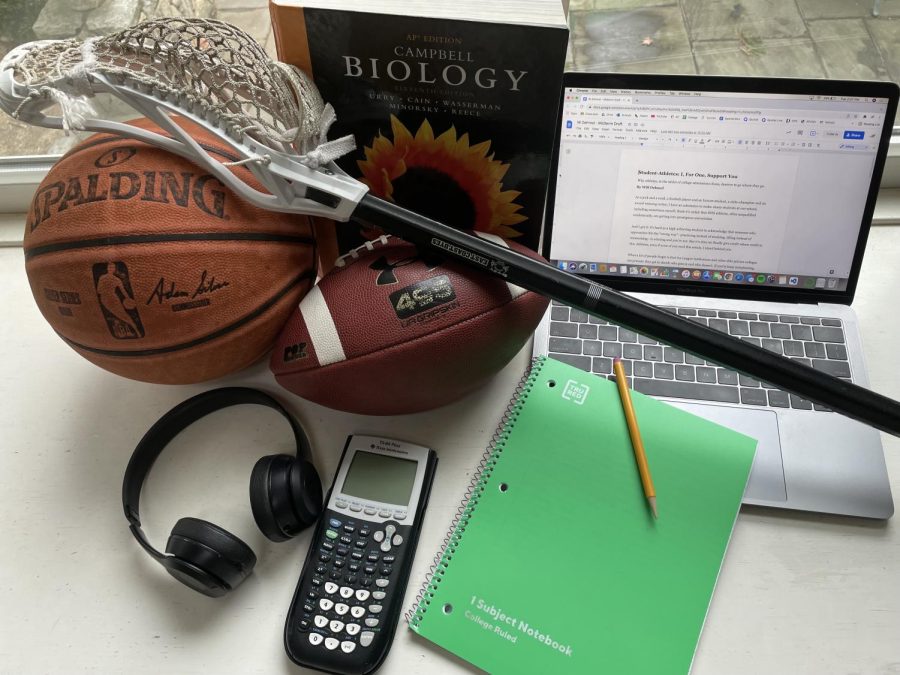

If the life of a student-athlete looks stressful, it’s because it is.

As a jock and a nerd, a football player and an honors student, a state-champion and an award-winning writer, I have an admission to make: many students at our school, including sometimes myself, think it’s unfair that DHS athletes, often unqualified academically, are getting into prestigious universities.

And I get it: it’s hard as a high-achieving student to acknowledge that someone who approaches life the “wrong way”—practicing instead of studying, lifting instead of memorizing—is winning and you’re not. But it’s time we finally give credit where credit is due. Athletes, even if none of you read this article, I stand behind you.

What a lot of people forget is that Ivy League institutions and other elite private colleges are private: they get to decide who gets in and who doesn’t. If you’re busy complaining, it’s likely because you know how incredible these schools are. And guess what: they’ve accumulated this success with athletes, and more often than not, because of them.

According to an article by College Factual, Yale football made $4,246,553 in revenue last year, all of which can be used for academic purposes. Not only that, but Princeton economist Harvey Rosen reported in a research paper written with Stanford economist Jonathan Meer that general alumni donations increase by approximately 7 percent when a “male graduate’s former team wins its conference championship.” So if Yale or other elite colleges want to make more money and improve their academic caliber, one answer is better athletes—it’ll lead to more revenue and, if the recruits live up to their hype, more donations.

Furthermore, in an era where diversity is so highly valued, it’s essential we not forget about the important role athletes play in adding to it. Even if Harvard finds itself with students of all socioeconomic backgrounds, races, genders, sexualities, and religions, it must not forget to fill its classes with students possessing varying perspectives. A 1600 or 4.0 or Scholastic medal or NASA internship isn’t all that students at Harvard should care about—sports, for many, is just as important.

As Chad Washington, a former football player for Columbia University, wrote in an article for the Columbia Daily Spectator, “during Friday nights in high school, [Columbia students] were probably in the library and not at the football game.” And while that’s perfectly okay, Washington astutely recognizes that “these students are distancing themselves from a huge and important part of life.”

When the intellectually elitist bubble of the Ivy League is removed from its recent graduates, many of their employers will be sports fanatics and care more about their social skills than the score they got on a single biochemistry exam. It’s important for impressive students to ride the cultural wave of sport before it rises up and crashes down upon them.

And while many, including The Atlantic’s Saahil Desia, assert the opposite, underprivileged minorities can absolutely get recruited in sports like football. Although expensive recruiting coaches can significantly help by reaching out to coaches and creating ideal highlight tapes, a great athlete with enough drive and determination can do that him- or herself.

Whether you want to admit it or not, student-athletes undoubtedly work harder than student-students. I’ve been in classes with top students and on fields with top athletes; being both is even harder. Ask my twin brother, who has one of the highest GPAs in the school and intends to join Dartmouth Football next fall as a walk-on.

As Kayla Abrams, a former rower for Columbia, wrote in another article for the Columbia Daily Spectator, rowers “wake up at 5:45 a.m. five days a week for practice,” then do everything a normal Columbia student does—classes, work, clubs, meetings—and then return “at the end of the day… [for] more practice.” I have to think many elite student-athletes agree with Abrams when she mentions it’s hard to “be[ ] the students our professors expect[ ], the athletes our coach recruit, the employees our bosses demand[ ], and the friends, classmates, sisters, and daughters that we want[ ] to be.”

And although arcane sports like rowing have high barriers to entry and therefore favor the wealthy, predominantly white members of society—think sailing, fencing, equestrian, swimming, and golf—we still must acknowledge the enormous effort required to excel at them. Plus, as Michele Hernandez points out in her op-ed in The New York Times, non-“helmet-sport” athletes are, on average, much more academically qualified.

But even if you can’t appreciate their efforts, remember that private institutions are private: they neither hold the only key to success nor should be responsible for ensuring social mobility. If you have a complaint, take it to the $53.2-billion endowed Harvard and see if they’ll listen.

DHS senior Will Dehmel started writing for Neirad in the spring of 2021. Aside from playing football, running track, and volunteering for DAF Media, Will...