When did Dishonesty Become a Victory?

Why a recent DHS scandal has precipitated a larger conversation on cheating culture.

June 8, 2020

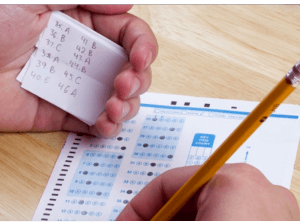

We’ve all seen the occasional side-eyed glance at a peer’s paper, or the all too well known “what did you get for number three” whisper, and we’ve probably all done it once or twice. However, a recent, and large-scale, Darien High School cheating scandal has received national attention, and has arisen controversy over the background and future of cheating culture in high schools.

According to local news outlets, including the Darien Times, Darien Superintendent of Schools Dr. Alan Addley announced to DHS parents that the multiple-choice answers for both the World Studies and English 10 midterm exams were breached and “widely distributed” to the sophomore class.

The scandal has sparked fervor amongst the hundreds of students who were forced to re-take their exams two weeks later, and hundreds of parents met to debate whether the alleged cheaters deserved more punishment than they received. Nevertheless, this transgression has precipitated an even larger debate that questions academic integrity and cheating culture not only at DHS, but nationwide.

DHS boasts some of the best public education in the country. With an average SAT score of a 1265 and 90% of students scoring a 3 or above on May’s AP exams, DHS academics are nothing short of rigorous. Students boast high GPAs and extensive extra-curricular participation, making DHS a poster-school for college preparedness. Or so we think.

If there’s one thing that today’s teenagers have learned from school, it is not literary analysis, calculus, or even life skills: it’s how to cheat. However, the blame for academic dishonesty does not fall completely upon laziness or lack of dedication; many students point a finger at an overly competitive academic scene when asked why they cheat.

A study conducted by “The Atlantic” in 2013 found that over 70 percent of high school students admit they have cheated, and 90 percent reported having copied another student’s homework. A high school in Long Island found in 2017 that multiple 11th grade students went as far as to pay others to take standardized tests for them, sometimes offering up to $3,600.

“It’s never justified to cheat,” said DHS sophomore Giselle Winegar following the recent scandal, “but DHS is such an academically challenging environment that some kids will do whatever it takes.”

Recently, academic excellence has changed from an appraised anomaly to a harsh expectation. Attending the most prestigious university is at the forefront of every student’s mind, as they have been raised by the school system to nearly inherently compete with their peers. As the result, hard work is no longer associated with intelligence; the only concrete evidence of success as it is defined today in high schools is the grade on the transcript at the end of the semester.

Some students go as far as asserting the moral right to cheat. A recent high school graduate told “The Atlantic” this year that he felt “cheated” of the education he deserved by the tests that assessed him. “I cheated to earn the grade I knew I deserved,” he added.

Many students think similarly, asserting that tests, strict rubrics, and cumulative exams would not accurately reflect their knowledge or academic proficiency, thus feeling entitled to cheat.

This argument undercuts itself, as if students constantly cheat in order to reflect the grades they think they deserve, they’ll never get the grades they do deserve. Academic dishonestly blurs the impressiveness of success. Students who achieve high standing class ranks by cheating often go as far as boasting about their grades, creating a false image of themselves for their peers, teachers, and even future college admissions counselors.

Another issue that arises from how widespread academic dishonesty has become is that these inflated letter grades and GPAs are taken at face value. Further, kids strive to please and often use that as justification. Straight A’s, they believe, will always strike a larger sense of pride in a parent than hard work, community service, or demonstrating a passion and proficiency in a sport or other extra-curricular. To a point, unfortunately, this opinion is not that far off from the pressure teens feel.

DHS junior Iyanna Green states that “its all about the letter grade” to parents and teachers; thus, kids feel pressured to get those grades in any way possible. Once A grades become associated with success, no matter how much the student behind that transcript truly deserves them, it seems as though the ends justify the means. This attitude is exactly what perpetuates corrupt cheating culture in classrooms.

This pressure to cheat, born from the academic rigor of high schools and competition among their students, causes students to become “incapable of actually processing information” says Green. Students become so accustomed to copying homework, using apps or websites to “cut corners,” and blatantly copying down answers on exams that they fail to learn how to study.

As much as high school teachers and administrations program their students to look towards an Ivy League education, students must be willing to fail. Cheating has been normalized to the point that hard work is no longer rewarded, although that is exactly what teens will experience as young adults in the work force: hard work, high reward. Teens, as morally incorrect as their academic dishonesty is, need to be told that struggling is okay. The student is always the cheater, but perhaps an unhealthy understanding of what education should be is the cause.