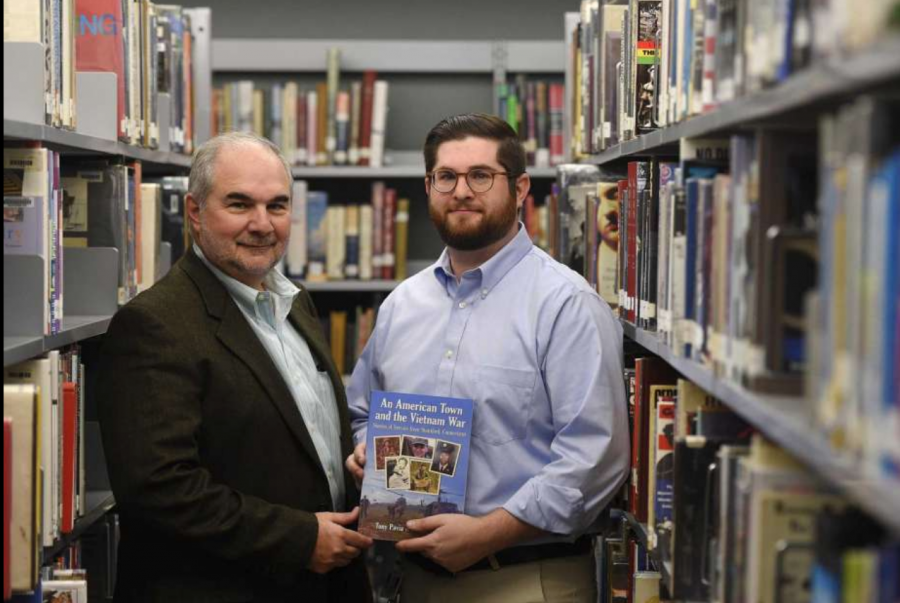

DHS Teacher Matt Pavia Publishes Book – Signing Tomorrow Night at Darien Public Library

“An American Town and the Vietnam War” by Matt and Tony Pavia

The American Northeast has historically been perceived as a breeding ground for the liberal elite, overall not representative of larger America. Darien High School’s own English teacher Mr. Matthew Pavia and his father, Tony Pavia, debunk this perception in their new book “An American Town and the Vietnam War: Stories of Service From Stamford, Connecticut”. The pair make the claim that Stamford, Connecticut, is a microcosm, a city representative of the demographics of the nation at large.

Neirad interviewed Pavia to learn more about the book’s content and inspiration. The book, says Pavia, “attempts to tell the story of America’s war in Vietnam through the experiences of people from one place in America… one representative city which… when you talk about race, religion, economics, class, all of that…really mirrors the nations demographics.” Focus on this specific American locale allowed the pair to dig deeper into local issues, and set the framework for the book at large.

“The book doesn’t take a political stance on the war,” says Pavia, “…it’s really just to say ‘this is from the perspective of this group of people from one place, from one time in America, this is what it is like’… it’s not about whether we should’ve been fighting the war or why we fought the war, it’s about what it’s like to be in that situation.”

A personalized narrative about such a broad topic required a long period of research. Pavia began this process at the Vietnam war memorial in downtown Stamford, a large stone monument containing the names of those killed abroad in the Vietnam war. From that primary source, Pavia tracked down obituaries, where he found the names of the veteran’s surviving family members all over the country. The co-authors reached out to every veteran and relative they could find for source material, but their research did not lie in interviews alone. Pavia recalls, “For a good year, my dad and I were both, separately, spending long stretches of time.. at the library in stamford… going through the [old newspapers] .” Pavia went through “every page of every day” of the Stamford Advocate and sources like it starting in 1964 and ending in 1973. This research targeted “any and all stories” related to the Vietnam war or the chaos of the 60’s and 70’s. Pavia kept true to his vision of the book, which both authors wanted “to be about the experience of …ordinary people (leaving) their lives behind (to) travel to a country across the globe and fight… in a war that was incredibly unpopular… and very ambiguous, even to the people fighting it.”

By focusing his research on personal experiences of the war, Pavia found himself conducting many interviews. “ [The veterans] are history,” explained Pavia, “We’re not making anything we’re just… preserving their stories.” These interviews were the most rewarding aspect of his entire authorial endeavor, despite the difficulty of tracking down his subjects. “There’s something about talking to people who were there themselves that gives you a completely different perspective,” he says. Pavia noticed the rewarding nature of the experience for those he interviewed as well, recalling, “I think in the end…it ended up being almost cathartic for the people themselves to kind of talk about it and then know that this story was going to be kept alive in some way”

This style of research gave Pavia a unique perspective, to say the least. In his interview, he was able to attest to endless interesting facts. “One of the big myths about the Vietnam war is that most people were drafted and went reluctantly, that not many people enlisted,” said Pavia. His studies revealed that most of these young men, having been brought up by World War II veterans, went willingly. Be they high school dropouts or men with jobs, all the media and rhetoric they consumed as children was centered around ideals of American patriotism. They went into the war proud to follow their parents’ footsteps and serve their country.

The disrespect and anger that characterized the public treatment of returning veterans stemmed from the fraction of the country’s youth that did not fight. “A lot of people couldn’t separate the war from the kids who were asked to go fight it,” said Pavia, reminiscing on stories of the disrespect returning veterans faced. “One (veteran) said he got off a plane… and they were throwing eggs at him,” Pavia recalled. Another had a basket of french fries thrown at his chest.

Next, Pavia discussed the writing process. “The hardest part was actually not writing the book… (but) getting started, finding a publisher, and then waiting.” The “middle part”, or the conducting of research and interviews, was rewarding for both authors. Pavia revealed that the pair started writing the book without any guarantee that it would be published, and gave insight into the process of finding a publisher. He began by working with a literary agent, who detailed the requirements any publication company would have for a pitch. Pavia described his proposal as, “basically… a synopsis…and an outline of the book.” He was also required to draft a comparative analysis. This entailed searching Amazon for any and all books similar in content to his, and determining how his work was unique. This functions to prove authenticity of thought to a publisher, but also to give the company an idea how many copies the book will sell based off others of its kind.

Pavia had one specific stipulation while negotiating his publication contract: no cuts. “We couldn’t stand the idea of having someone spend 3.5 hours with us talking about these very personal, very serious, very sad memories- painful memories- and then saying ‘sorry you didn’t make the cut’,” asserted Pavia. This accounts for the books length (273 large pages of small font). Not a single interview was cut.

The process after the manuscript is submitted is incredibly stressful, authors going long periods of time before getting word from their publishers. “Every once in awhile someone would get in touch with me and I would have to release permission forms for the photos we were going to use…or I would have to do the index for the book. Little things like that,” said Pavia. However, it isn’t all bad- “You get five free copies if you write a book!”

With the bulk of research, writing, and publication struggles behind them, the co-authors arrived at their publication. The official launch party took place on November 14 at the Ferguson Library, in Stamford. There, the pair gave a presentation and signed copies of the book. In an attempt at unifying and reconnecting with all those involved in the book, Pavia invited each veteran and family member he interviewed to attend a get together before the launch. Each of them received their own autographed copy of the book, as generously donated by Grade A, a Stamford grocery store. “We saw this idea of getting… as many people as possible in the room together and saying ‘hey guys you all have something really important in common’ and just to thank them.. for trusting us with these very painful and personal memories,” said Pavia. His goal was to encourage them to use the important experiences they have in common to form connections, as many of these people, having left Stamford for the far reaches of America long ago, have never met. Individuals flew in from such lengths as Alabama, New Mexico, and Seattle for this event alone- no small amount of pressure for Pavia. In addition to the festivities on the 14, there will be a signing at the Darien Library on December 5 (click for details). Neirad encourages students to make it out to show support for their teacher.