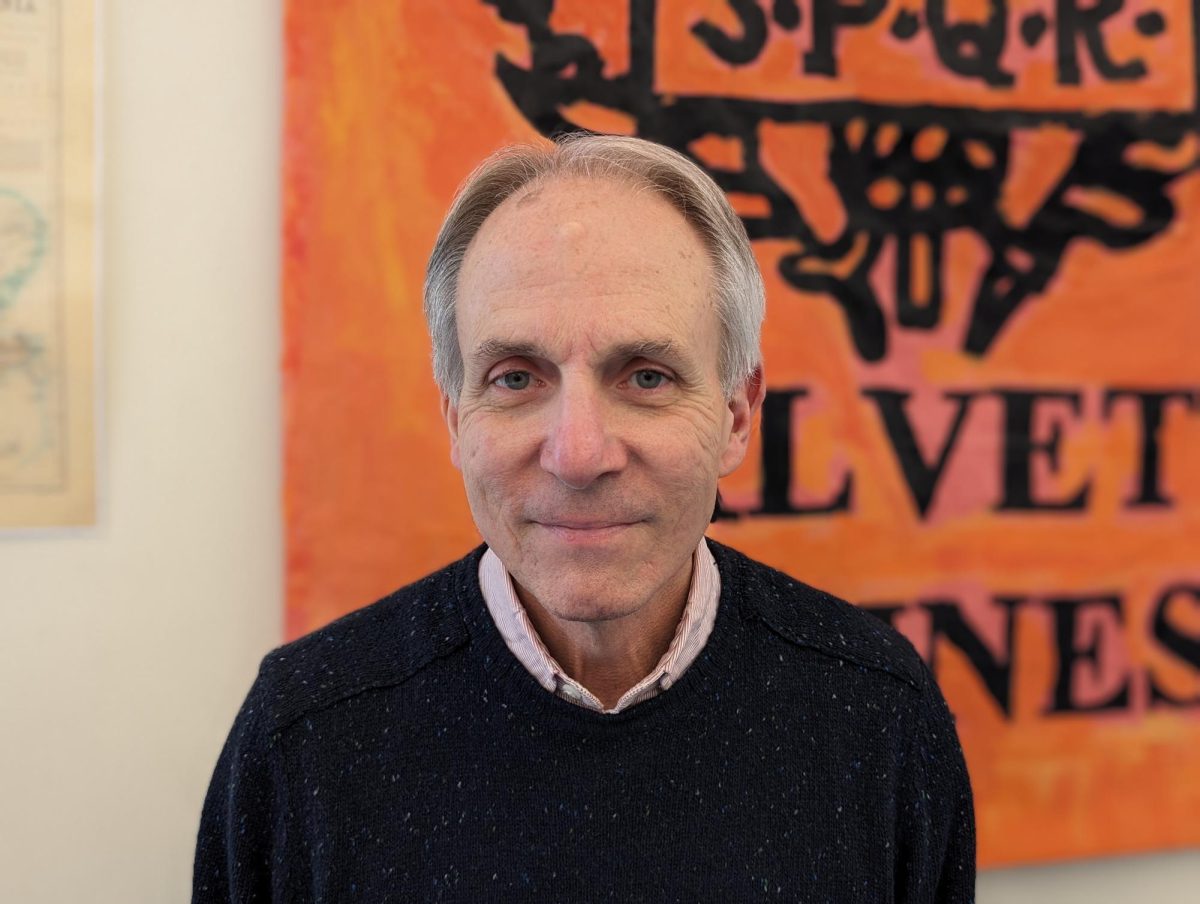

When I asked John Gearty, a Darien High School Latin teacher qualified to teach all four levels and who often teaches three in a given year, if I could interview him on a day’s notice, he replied within an hour. I met with him the next day in his classroom, all the while seeing the attentiveness that his students appreciate greatly.

This enthusiasm, he says, comes from his own lifelong study in the language, for no classicist truly stops learning in some way. Gearty’s mission is to bring Latin to new generations. Whether they come to his class with this fascination or not, he wants “to re-create, as best [he] can, a world in which people can feel as if there’s a lot for them to investigate if they choose,” he said.

His own journey with Latin started in the Catholic Church. Gearty was raised in the years when the Latin mass was still widespread, serving his congregation as an altar boy. This, he recalled, involved dialogue with the priest and congregation in a language new to him but alluring from the beginning. This involved memorizing and reciting passages from the liturgy of the mass.

“I can say that Latin was truly my second language,” Gearty said.

Though the Vatican, Latin’s chief protector over the millennia, started approving greater use of local vernaculars after 1970, young Gearty found his interest in Latin broadened by the new chance to live amidst an ancient culture. Gearty’s father was a diplomat, his assignment to oversee U.S. foreign aid to Egypt. During Gearty’s first two years of high school, the family lived in Cairo, known as the city of the Great Pyramids.

“[Egypt’s] being so old, you can really pick your historical period to study, and it’s going to be fascinating,” Gearty said, referring to the times of the Pharaohs, Greeks, Romans, and caliphates—“people and events that were much prior to our time.”

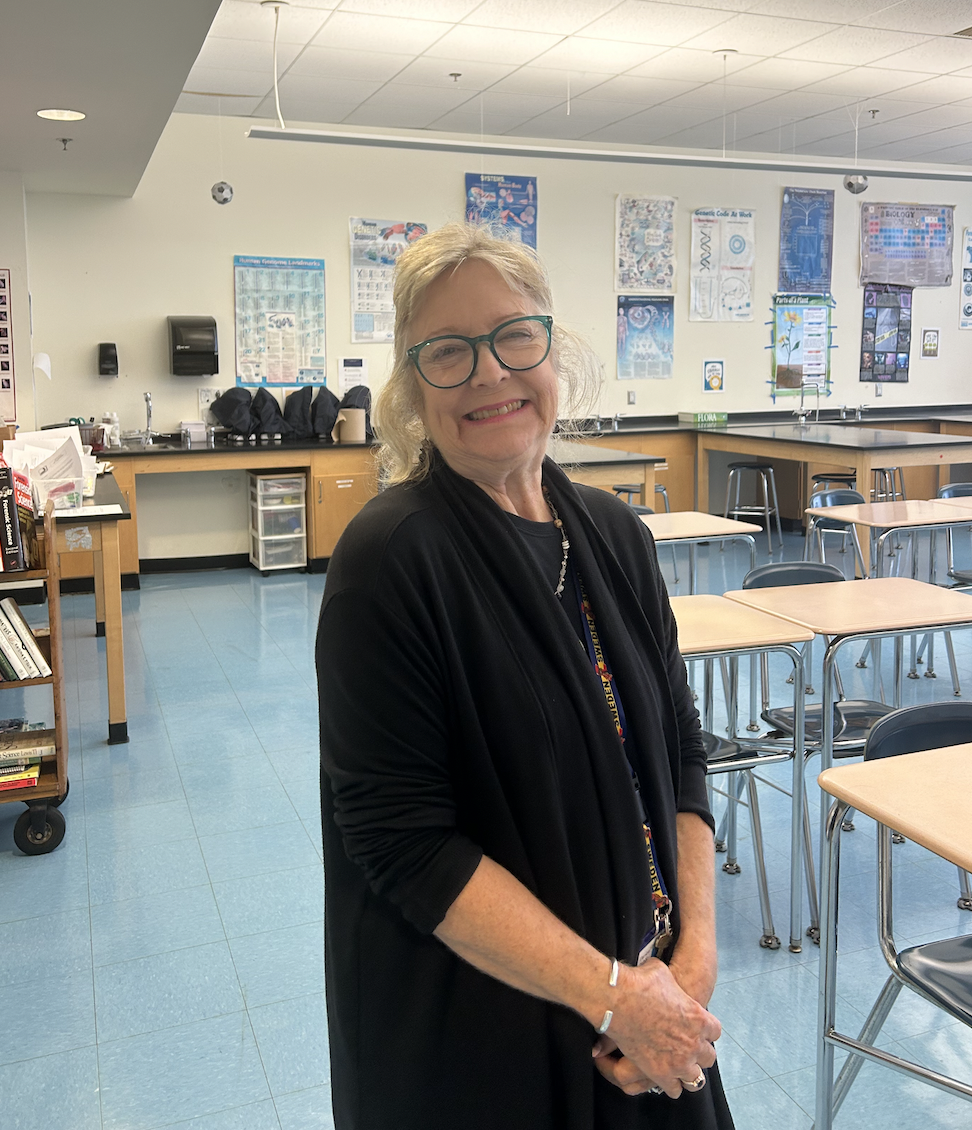

Hearing how early he began his study of Latin, I asked him whether the same could be viable for students at Middlesex Middle School, where he has focused much of his recent advocacy for learning the language. He was quick to counter the common assumption that I myself held: that one cannot understand Latin without learning one of its living descendants–such as Spanish, French, or Italian–first.

“I don’t think, especially if you’re starting at a younger age, that you would do badly at all to just begin with Latin,” Gearty stated.

College Board advises that a Latin option at a younger age, in the same way as French, Spanish, and now Mandarin, would open up future high schoolers to advanced options down the line, including AP Latin. Of course, all language programs, especially at younger levels, hinge on student demand.

Because of this challenge of demand, many do believe that studying a “dead language” is simply imposing an unnecessary burden on oneself. However, Gearty said that Latin is very much in use today for reading, writing, and analysis of topics both ancient and modern. So too is it a misconception that linguistic differences hinder rather than enhance communication, he said. Instead, he believes as I do that languages are the gift of human diffusion around the world—as varied as the minds of their speakers past or present.

“Languages are just like that,” Gearty said. “They grow up, and they’re distinct, and they’re—by definition—carriers of different experiences.”