Let’s Resort to Education, Not Persuasion: Nutrition Education in American Schools

As both obesity and eating disorder rates soar in the U.S., it’s time to take a closer look at nutrition education in American schools.

How do you teach kids to be aware of what they eat without pushing them toward an eating disorder?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 18.5% of American children are obese. At the same time, per the Polaris Teen Center, 50% of teenage girls and 30% of teenage boys use unhealthy weight control behaviors ranging from skipping meals to over-exercising.

So, while we ought to focus our attention on nutrition education in American schools, the attention has been aimed for a long time at the wrong objective: increasing nutrition education rather than improving nutrition education.

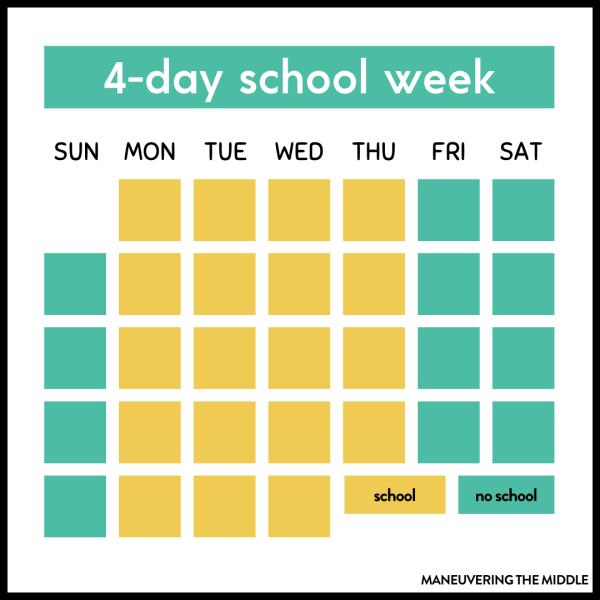

Unfortunately, we’ve missed even the misaimed goal. The CDC reports that the average American student receives less than 8 hours of required nutrition education each year, a number far below the 40 to 50 hours that scientists agree are needed to affect behavior change. To compound this, from 2000 to 2014, the percentage of schools requiring instruction on nutrition decreased from 84.6 to 74.1 percent.

Still, this epidemic won’t be solved by more nutrition education but by better nutrition education. Because it’s getting worse. As the Institute of Medicine puts it in their book Nutrition Education in the K-12 Curriculum, “the emphasis in nutrition programs has moved from micronutrients to the amount and variety of food,” an emphasis that gives the personal bias of teachers power over a set of facts given to students for students to interpret on their own.

Nutrition education has transitioned from teaching students the importance of certain vitamins and minerals to teaching students, albeit in disguise, to diet.

As a student who has gone through my public school district’s nutrition education curriculum, I can confirm this transition. I can vividly recall seventh grade, when I was taught ways to limit portion sizes in health class, like using smaller plates, and was asked to label foods as ‘saludable o no saludable’—healthy or unhealthy—in Spanish class.

Unfortunately, my experience is no anomaly. Six-year-old Emerson Kiarie of Montclair, NJ spent class time sorting foods like watermelon and donuts as healthy or unhealthy. Across the country in Denver, CO, 15-year-old Katie Ralston was assigned the task of counting calories using a food log for two full weeks.

It should come as no surprise, then, that dieting among children is rampant. The Institute of Medicine states that “many children in middle schools and even some in elementary schools say they are dieting.” More alarmingly, according to a University of Michigan Health System survey, after participating in bodyweight measuring and calculations of body mass index (the number responsible for labeling an individual obese), 30 percent of parents reported noticing in their children at least one behavior that could be associated with the development of an eating disorder.

Nutrition education focuses on instilling fear in students of weight gain, culminating in 81% of 10-year-old American children being “afraid of being fat.” In doing so, it simply swaps out one horrible problem—obesity—with another horrible problem: eating disorders.

What’s perhaps more important to note is that there is no objective definition of healthy. Merriam-Webster defines healthy as “beneficial to one’s physical, mental, or emotional state.” The large majority of nutrition education in American schools focuses entirely on students’ physical health without taking into account that students’ mental and emotional health are not only equally important but can, if awry, cause students’ physical health, too, to go awry.

Given this logic, schools shouldn’t be giving students any advice but instead education that lays out the facts and allows students to interpret them on their own. Education that informs students rather than incites students.

The best way to do this is to teach through experimentation. To go along with CDC recommendations, schools can find creative ways to expose students to ‘healthier’ foods by offering farm-to-school activities, having students work in school gardens, and putting fruits and vegetables in noticeable areas of the school cafeteria. Schools shouldn’t preach that students exchange the donut for the apple but actually give students access to the apple.

Like schools throughout the world—like France, for example, where students enjoy a lunch menu of beet salad, pumpkin soup, and veal stew—we can teach students that fruits and veggies can taste good by including them in delicious, high-quality meals.

Admittedly, we cannot expect all children to eat “salad like it [is] going out of style” and “peas like they [are] the best thing they had ever tasted,” as children did when Michelle Obama hosted children at the White House Garden as part of her Let’s Move! campaign. But allowing students to try healthy food in an appealing manner can have major consequences in the long run.

It’s one thing to teach about a food being healthy in the classroom. It’s another thing to prove that it can taste good on a plate.

To do so, we need to focus on allocating resources to school cafeterias. Schools receive $2.68 for each free meal served through the National School Lunch Program. Accounting for labor, facility, and structural costs, schools are left with little more than a dollar for the actual food. Making meals with organic, ‘healthy’ ingredients is impossible.

Even teachers are on board. According to Improving Nutrition Education in U.S. Elementary Schools: Challenges and Opportunities, 70% of teachers prefer nutrition education that contains a school cafeteria component.

In a country founded on freedom, we have to stop telling students what or what not to eat. What we can do, like teachers do every day in every other class, is not force students to improve themselves but provide them the tools to do so.

We can resort to education, not persuasion.

Senior Luke Dehmel began writing for Neirad this fall. You can find him on the football field, the track, at the NEHS Writing Center, where he tutors,...